|

After being away from class for a few days, I received a not so positive note from my substitute teachers. My first reaction was "how embarrassing." My second reaction was "really, you did what?" And finally, I asked myself, "can I hit the re-set button?" The instructional coach on my campus wrote about the "re-set" button in a newsletter she sent at the beginning of the semester. I did not think, at that time, it was necessary for me and my students. We have a positive rapport and work well together - but being absent for three days indicated something had gone awry. My students seemed to forget about our agreements with regards to technology use in the classroom, which required that I come back to class with a better plan. This is the first year I am working in a 1:1 setting with a cart of Chromebooks. There have been some great advantages to this, but I realize that my students have never been challenged with integrating technology for educational purposes. I started searching for some inspiration and found a great site on Edutopia dedicated to the question: Are we addicted to technology? I used some of the resources to begin a conversation about effectively using devices in the classroom. We started by watching this video: All of my students (juniors and seniors) laughed at the ridiculous situations presented in the film clip. They thought the representation was a little exaggerated - but then thought about their own actions in class. I asked them to make a T-Chart labelled "Appropriate" and "Inappropriate" so they could identify ways technology is used in academic settings. They quickly came up with a number of ideas; however, I challenged them to re-think the "inappropriate" category. This was a trick question as I was trying to get them to think about the purpose of technology and how our academic goals shift the use of devices and apps. Many of the items they deemed "inappropriate" could be shifted to the other column after careful application. The goal of this task wasn't to limit our use of tech; instead, I think this was the first time my students were even included in the conversation about the use of technology. Removing tech was not my goal. Actively reflecting on learning and the integrations of tech was just the start.

We then took some time to read an article called "Are You Addicted to Your Phone? Change Technology Addiction? Immediately one group piled their phones in the center of the table - taking a hint from the article. I told them that my friends and I had also done this when going out to dinner: all phones piled in the center of the table and first person to touch their phone pays. It was an effective strategy. This mini-lesson helped me hit the re-set button in our 1:1 classroom. Are all of the issues fixed? Definitely not. Will my students act differently the next time there is a substitute teacher? Hopefully. While the dance party was probably entertaining and when the FAFSA rap they wrote went viral on Snapchat at our school, I knew the sub must have been at his wits end. In fact, my students inspired me to help them create a project using social media in order to share about the FAFSA and CA Dream Act. That's in the plan for the next couple week. I'll post some examples soon. This situation reminded me that I, too, make mistakes. I admitted that this tech issue was partly my fault. It's never too late to hit re-set.

0 Comments

In the last few years, I have really struggled with the fact that my students endure a lot on block schedule - and by a lot, I mean time and sitting still. While I love having 96 minutes for each class, I wonder if I am using the time effectively and if my students are engaged. In conducting some research about classroom environment, mastery grading, and flipped classrooms, I asked myself: Would I want to be a student in my own class? This question also has to do a lot with the content. I primarily teach United States history and I know how many students say they hate history. And I actually like that - it gives me an extra challenge.

My passion for critical pedagogy and the writing of Paolo Freire encourage me to constantly reflect on my teaching, what I say in class, and how the instructional strategies I choose have an impact on students. I am not talking about the purely academic effect. Instead, does my pedagogy align with a critical stance on education where learning occurs through reciprocity between teacher and student. Do I value my students perspectives and challenge traditional classroom structures that give the teacher complete power over knowledge dissemination. Do I provide students with the opportunity to engage their own backgrounds and experiences to make learning more about the exploration of self and not just content? Are my beliefs about the power of education apparent or am I a little delusional in the sense that there is a disconnect between what I want to have happen in class and what is really occurring? So again, would I want to be a student in my class?

Next semester I want to conduct my own mini-research study. I want to video record my lesson plans and spend some reflecting on what really happens in 96 minutes:

This deeper analysis of my teaching might lead me to find better ways of aligning my philosophy of education with my practice. Some of my colleagues get annoyed when I talk about education theory because they struggle with getting stuck in the world of ideas and what ifs. However, I would argue that all of our teaching is grounded is some theory. We just might not be aware of what ideas and beliefs we reinforce or replicate. I have appreciated so many of the great discussions on Twitter and blog posts about the renewal educators get after winter break. Two weeks is just enough time to refresh our thinking and get excited about returning to the work we do with our students. They probably need the break too, not gonna lie.

But in the last two weeks, as I have continued to pursue my own personalized PD, I realize that this is something very few of the teachers on my campus embrace. As I go back to school tomorrow, many of my goals for 2016 focus on building stronger relationships with my colleagues and sharing what I have learned by being a connected educator. Here are a few of my ideas & goals: 1. Make the walls invisible. So many teachers, especially at the high school level, work in isolation. Three of the four subjects I teach are only taught by me, which means looking for a community of learners is necessary. But even in course alike team, high school education has been so compartmentalized that teachers operate in their own worlds. As the Teacher Technology Leader and AVID Coordinator at my site, I need to seek more ways to work with teachers on a regular basis.

2. Share. Teachers attend so many meetings where nothing gets accomplished - hopefully the last two I mentioned don't end up that way. But what I can do is encourage teachers to share information through digital tools we can available.

3. Host a Twitter Challenge Twitter has honestly changed my world as a teacher. The ability to connect with educators across the world for questions and lesson plan ideas I'd like to share the uses of Twitter by teaching about how to communicate with students and how to participate in #chats.

4. Branch out. In addition to being connected through social media, I have found the support of professional organizations to also be helpful. Some teachers do not enjoy face-to-face conferences, usually because they are forced to attend. However, the conferences I love to attend are hosted by organizations that I value. I also find that presenting at these conference are the most rewarding. The feedback from teachers who love teaching and who choose to attend conference is amazing. I am going to continue presenting at conference and writing for academic journals. Here are a few organizations of which I am a part:

These are just a few of my ideas, but I am sure they will grow more complex as I get inspired by continuing my own pursuit of being a connected educator. I hope that other teachers start to build networks that support their own professional development in order to improve teaching and learning.

It's been two weeks of winter break and as I head back to class in a few days, I started to stress a little about the DBQ my students were supposed to write during vacation. I know, never a good idea. It's not really due until later next week, and honestly "due" is a relative term. I am not too strict on due dates because some students just take longer to get formal writing done.

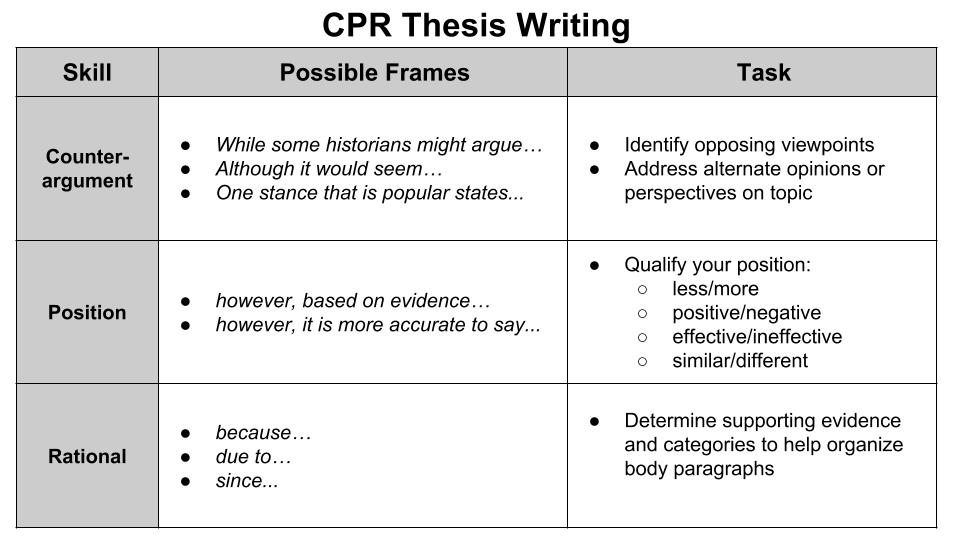

As soon as we get back, I am going to spend the last couple of week before the end of the Fall semester reviewing some of the essential argumentative skills we have been practicing. In this post I want to highlight one of the strategies I have used to help students construct organized argumentative thesis statements/essay responses. And the new APUSH writing rubric give up to two points for quality/complex thesis statements. The first is the CPR Thesis Statement. In the past I have used the Sheridan Baker Thesis Machine but found that the steps confused most of my students. They understood the concept, but somehow the directions were never quite clear enough. The procedural development of thesis statements made some students uneasy. As I have learned in the process of doing group writing and individual responses in class - writing is messy. Teaching on-demand time writing in my AP United States history class is tough because it is a skill that is rarely practiced in any other context (nor do I think it will be used much in the future - but that's a whole different discussion). Even my own writing getting to the central argument takes time and work piecing the right words together. So rather than teach the process in steps, I created a chart that focuses on the product. The CPR Thesis, seen below, is very similar to the Thesis Machine. I should thank one of my colleagues, Sara, for developing the idea and sharing it. The chart has made thesis writing more about the parts of argumentation. However, this type of thesis doesn't work well with all prompts so I always tell students that the "counterargument" could look different. The frames are there as examples. When practicing thesis writing in class, my students often use alternate sentence constructions, which is great! These are just a starting point. Below the CPR Chart is a Google Slides presentation I used to introduce the process to my students. There is a sample we wrote using an article about the effects of the Columbian Exchange. As a school site, we developed a writing handbook to help students in our History/Social-Science classes. This is definitely one page that students use often. Why dystopia?Utopian and dystopian studies comes from a deeply historical context whereby people of all walks of life began imagining possible worlds where political, economic, and social conditions were altered. In United States history, utopian novels that were published during the antebellum age (1820s and 1830s) espoused the possibility to re-imagining social order. Communities built by the Shakers and Oneidas lived out their utopian dreams. Dystopian literature, burgeoning during the late 20th century reflected an increase in fear about political and economic turmoil. Novels like 1984 and Brave New World emphasized the relationship between power, technology, individualism, and conformity. Resistance and reform had a very different face after the social movements in the 1960s and 1970s. Dystopian novels play with constructs of time, space, history, and geography. The worlds seem so much like our own or at least what our world can be. While many of the novels written in the Cold War era reflect fears about conformity, dystopian novels written in the early 21st century engage these topics a little differently. Surveillance and ideological repression look different in 2015 than it did at the height of the Cold War. The battle between capitalism, socialism, and communism has been subsumed by neoliberalism and globalization. One person standing up for what they believe triggered marches and protests that were televised around the country in the 1960s and now one Tweet or YouTube video goes viral where the world is now watching global affairs. YA dystopian novels are unique in that they center on the actions of youth as they participate in resistance against totalitarian leaders. Each novel's world is constructed on some kind of sameness or conformity. The hero's or heroines never quite feel like they fit in with the communities expectations and they often find ways of escape expectation. Rather than accepting societies norms, that main characters question their world and seek alternatives. But no dystopian novel is "perfect," Some might say that the genre is itself a tool of resistance whereby authors offer social criticisms of our own world. However, a deeper analysis could reveal that the novels only reinforce some of the underlying economic and social tensions that youth experience today.

I believe that history teachers can use dystopian novels to help students see history in action. Sometimes history curriculum seems boring or outdated. Despite what some might say about the literary quality of some young adult novels, I find that dystopian fiction provides a doorway to connecting our students to our content. The language and vocabulary is similar between the novels and history curriculum. We can engage students in discussions about the past AND in imagining the future by integrating fiction into our classrooms. Books vs. FilmsAfter taking a Film & Literature course in college, I stopped making broad assumptions and arguments about whether or not the book or the movie was better. Essentially, it is like comparing apples to oranges. Privileging one over the other de-values both as artistic representations and tools of storytelling. Are there times where I enjoy the book more than the film, yes. But there are also films that do an amazing job in adapting novels so that my enjoyment and appreciation grows and changes. We have to view media as separate because they each have different goals and achieve those goals using different tools. We can study films in a similar way that we study novels by questioning narrative structure, format, characterization, and themes. Novelists work with words whereas film makers use music, sounds, and color to tell a story. Questions to be asked of dystopia & history curriculumPower

Knowledge

Surveillance Culture

Codification & Discrimination

Post-Capitalism & Consumerism

Novel ideas

Dystopian shortcomingsMy final thoughts come just after seeing the final installment of the Hunger Games films that opened this weekend. After reading 20+ dystopian novels (marketed for adults and youth), I have been left with one question: what happens after the rebellion? Almost all of the novels focus on resistance efforts led by characters who do not agree with the government's actions. But what is missing is any notion of HOW TO REBUILD. People join resistance movements to fight for their rights. Totalitarian governments are deposed. Evil leaders are killed. But the books and films always end there. There is no transfer of power. There is no explanation for what kind of society is re-imagined. The heros and heroines go home and live their lives out of the spotlight.

This feels exactly like a traditional history classroom. We spend time studying events of the past and do little to institute changes that will make the world more equitable. We fail to act on our knowledge in creating a better world. I love reading dystopian fiction because I get to engage in imaginative worlds that challenge me to think about our own. But we can't stop at resisting. We must also engage in creating and imagining. Warning: Part 1 of this post is a political statement. But... Part 2 will have some lesson plan ideas. Civic ImaginationWe live in a time (as was the same with our predecessors) where we are inundated with tragic events that seem to highlight the angry, competitive, frustrated, and hateful aspects of human interaction. News media frames the human experience by focusing on sensational events. And by no means am I devaluing horrific situations that occur across the world in Syria or France, or even here in the United States. What I want to highlight is the need for a shift in our thinking about history and history education. While I watch the education pendulum swing towards STEM, no doubt because of the high demand for job applicants in related fields, what most ignore is how the pendulum swings away from humanities courses like history, political science, sociology, and literature. I struggle to support an increased emphasis on STEM based on an economic argument. The increasing wage gap and opportunity gap between economic classes, people of color, and genders continue to widen despite the push for STEM in schools. We need a more radical approach in dealing with constant conflict and debate regarding income disparity, race wars, police brutality, gender discrimination, and religious fundamentalism. I truly believe that we are at another crossroads for history education. Because of heightened awareness regarding political, social, and economic conflict, NOW is the time we must engage in a new kind of historical thinking. I remember studying history (sometime guilty because I teach history) as an object of the past. People before us made decisions that caused our current situation. Some historians might think that I am erroneously encouraging presentism; however, I believe that we need a way to talk about history as if we are creators and dreamers. We need to think about history, not just in the past, but as an analysis of the present and most importantly the chance to imagine possibility. What is the point in studying the past if there are no effects on our present lives and the world we have the power to create? My first goal in exploring this topic is to talk about, what Henry Giroux calls, "civic imagination." Many teachers feel that their classrooms have been drained of creativity, imagination, and free thinking. Increased "accountability" measures have tremendously affected what we value as knowledge and what is taught. As history teachers, we have focused on memorization and recall that our students do not even practice the act of engaging as historians. This idea is shifting as more research is being done with respect to thinking, reading, and writing like historians. However, I believe these skills still limit our understanding of history as the stuff of the past. We need a language that engages our ability to think and create. We need a driving force that encourages hope through the language of possibility. We need to practice building our civic imagination where our students are building relationships based on respect, equity, and justice. Civic imagination is connected to civic engagement, whereby our students see action as a necessary step is studying history. We can't just think, read, and write. We must also do. Giroux says we need a "radical imagination" that encourages civil literacy and provides opportunities for personal and social transformation. Here is an excellent passage that summarizes Giroux's point: "The importance of civic education in the shaping of democratic values and critical agents cannot be underestimated and functions as the basis for developing specific modes of resistance and larger social movements. Cultivating the radical imagination, civic education and engaged and critical modes of literacy and agency are central to producing an informed citizenry, but even more so to constituting any viable notion of politics. Education must be considered central to any viable notion of politics. This suggests that progressives make clear how cultural apparatuses and media sources work pedagogically to produce market-driven subjects who are summoned to inhabit the values, dreams and social relations of an already established repressive social order [....] The time has come to develop a political language in which civic values, the radical imagination, social responsibility and the institutions that support them become central to invigorating and fortifying a new era of civic courage, a renewed sense of social agency and an impassioned political will." Framing Our LessonsFrame #1 - So What? One challenge I am beginning this year is to add a "so what?" question at the end of each class. My hope is that my students and I can make direct connections between the content we cover in class with current events. So many of my students say they do not see the point in studying history. Adding the "so what?" will hopefully ground the content in contemporary contexts. So when we are studying federalism, the first Two Party system, and the debate between Jefferson and Hamilton, all I have to do is turn show a clip from the current GOP and Democratic presidential debates and highlight the arguments about the power of federal and state governments. We can talk about the legalization of same-sex marriage and marijuana as conflicts regarding governmental powers. This first frame indicates the importance of using current events in our history classes. Frame #2 - What if? An additional question we might ask of our content is "what if?" an event in history or a person's decision had a different outcome. This line of questioning directly infuses civic imagination whereby students are imagining new and possible worlds that are dependent on significant political, social, and economic choices. This question blurs the lines between fact and fiction. Some history teachers might fear when students reach into the future to imagine what would happen if Hitler had won World War II. The purpose of this question is not to re-write the past. It is instead of find what I call "points of divergence" so that we can write the future. We are the lives of history. Our choices have a profound impact on what the world will look like tomorrow, next year, and in 100 years. The people we study in history had this same idea. FDR imagined a different United States than the one that existed after the stock market crash in 1929. It took the imagination of numerous people to foresee the effects of the New Deal. Frame #3 - Now what? The last question I want to ask in my planning is "now what?" How can we make history a subject that encourages participation? In the last couple years, there has been a push for civic engagement (C3 Framework) and defining what it means to be an engaged citizen. I am wary of the use of the word "citizen" in this framework, but I also have this same fear with the term "digital citizenship." This is due to my experience teaching in a community where many of my students are undocumented and will never have the chance at becoming "citizens" based on the current political climate. It makes me uncomfortable to teach the concept of "citizenry" when the idea remains an illusion or an unreachable goal for many students. However, I do believe that the qualities outlined in the framework are valuable - my objection is purely based on language and the effects word choice have on people's inclusion or exclusion from identity membership. Asking "now what" allows me to encourage students to see history as action. We need to think about action steps that can accompany our study of historical events. We constantly talk about people who did something in history, but often fail to encourage action as a responsibility. One organization that has helped me think about the value of student voice and student perspectives is SoundOut. Our schools and communities would benefit from responsibly and ethically implemented student-led research about our local communities and what can be done to change the world,one choice at a time. Next StepsI am working on some concept maps that can be used to help frame history lesson plans using these three questions. I am also working on some graphic organizers and instructional tools that will engage students in the kind of thinking and doing proposed.

But the most important work that I am completing right now is my doctoral dissertation. I worked with a group of eleven high school students to examine the significance of dystopian fiction and how fictional narratives influence our thinking about issues related to identity formation, power struggles, and resistance movements. There were some great findings associated with the use of dystopian fiction in history/social science classes that engage in the three questions I highlighted. More on this to come. If one were to visit the "traditional" history class, you might find the teacher at the front of the room pointing at the PowerPoint slides while students copied down whatever information was posted. (Side note: Why do we have students copy notes when it would be much easier to share them online or just print a copy?) This kind of classroom - influenced by industrialism and economic necessity - ends up being a dumping ground of information.

I'll admit that in the last few years I have begun to really questions some of the "traditional" tasks that I forced students to accomplish. The first time I taught AP United States history, I required my students to memorize all of the Presidents, their political parties, and years in office. It was a fun challenge and I enjoyed watching students write stories, make dances, or memorize what sounded like binary code to pass. It was a 100% or nothing quiz but they could take it as many times as they want. Finally, a couple students asked me if I could pass and I admitted: absolutely not. Then why give it? Do they really need to memorize all of that information? If I needed to remember when President Jackson was in office and who succeeded him, I would just look it up on Wikipedia. There are so many questions that we have about history. Granted, I remember a lot of information because I teach the subject year after year, but there are times I am stumped. And each year I have to review those topics that I don't really like. Yes, there are historical topics I don't enjoy (sorry American Revolution & Civil War historians). So instead of focusing my attention on getting students to memorize, I started looking at flipped learning and really teaching about access to information. Rather than reading every word of the textbook, I recommend a shortened version in combination with support videos. In class, we focus on activities. I love using discussion models, word sorts, map activities, sculpture, visualization methods, etc. It's in class where I can watch students struggle with content and learn how to mine the massive amounts of information to decide what is most important. To teach about primary source documents, I developed a structured discussion protocol. I will be presenting it at a few conferences this year and hope that it might be helpful in any history class. My presentation and resources are linked here. This activity his pretty intensive, but it really challenges students to become the historians. They can focus on a text and dive into the author's or artist's world. The structured academic discussion I will be presenting is just one model that I use in class. I find that using protocols requires students to synthesize a lot of information into a very focused and purposeful discussion. And in the last few years I have seen some (slight) improvement in writing. The link between speaking and writing is sometimes absent in classes. Teachers often skip from reading to writing and forget that there needs to be time given for students to talk about the content. I'll admit that I am a theatre enthusiast. (only wish my budget allowed me to see more productions that come to Southern California or take some weekend trips to NY just for fun). But as a teacher, I am always looking for alternative texts and narratives that tell stories in different formats. Students are inundated with texts - in class, in their community, on their phones, on television, at home, etc. But very few of my students have the opportunity to experience live theatre. Having participated in drama during high school, I developed a profound appreciation for the intricate details that go into a fully staged production. Plays and musicals are more than just actors on a stage. Sometimes a show is produced that has a profound impact on my understanding of historical narratives, whose story is told, and what that story means to us today. In this post, I want to highlight four musicals that continue to fascinate me and renew my thinking about the past sneaking into our contemporary world. Hamilton

Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson

Ragtime

Miss Saigon

There are, of course, many other musicals that could be used in history classes. We can look at these musicals as texts themselves: how do the lyricists and composers interpret historical events or how do actors/actresses portray historical characters? How can we use historiography to explore the narratives told (or not told) in these musical interpretations?

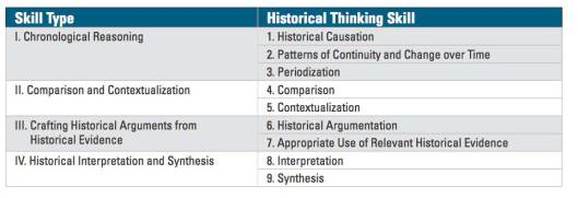

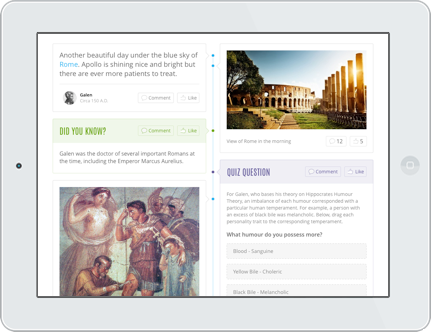

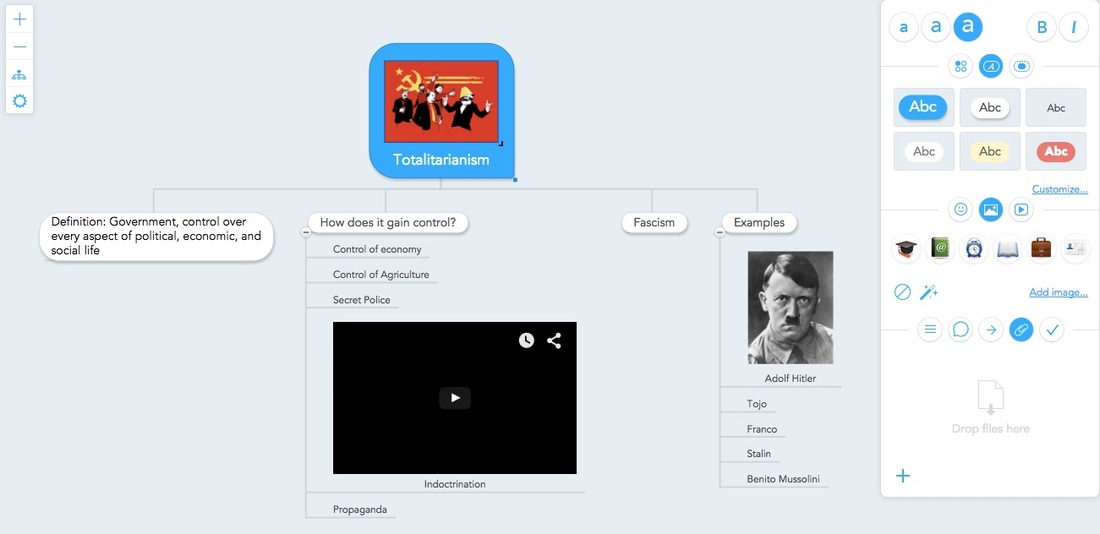

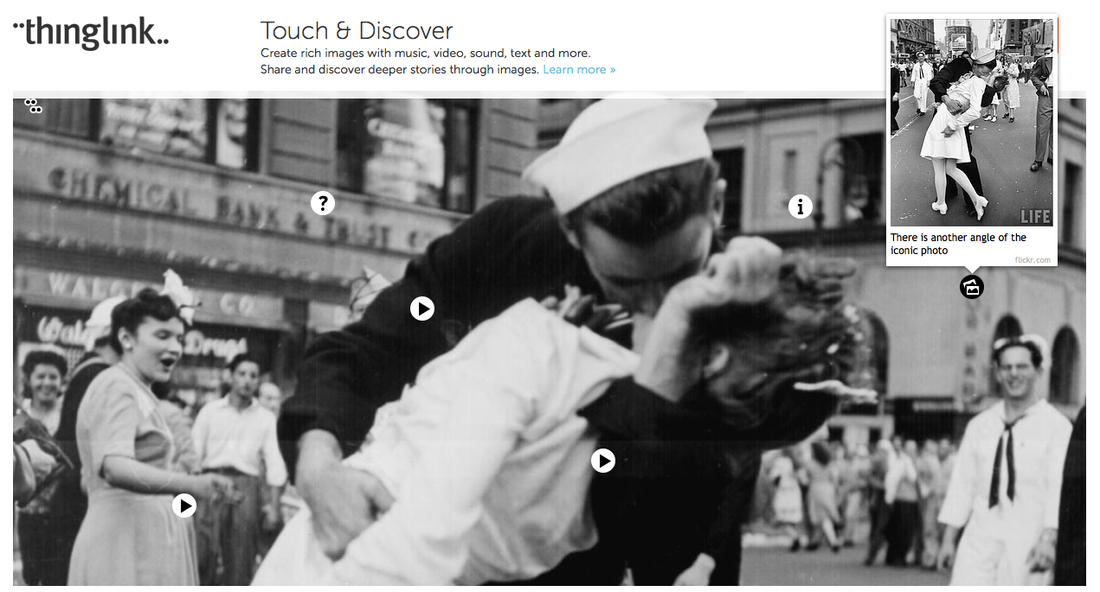

So I walk into a classroom during #Edcamp605 on Saturday and I honestly didn't even know the topic. I was chatting with a fellow participant and he said the session title was "Inquiry." I said, "okay, sounds interesting." Lo and behold, the first five participants that showed up were all history teachers (middle school, high school, APUSH, AP World, and AP Gov all represented). We engaged in an hour long discussion sharing ideas, questions, and frustrations. A few more teachers came in as they were lurking on the shared note-taking form when they saw we were talking about history classrooms. This is such an important discussion considering the present state of history education in many states. In California, the History/Social Science framework is being re-written, the content standards remain the same, and there is currently no end-of-course assessment at any grade level. This time of flux is both enlivening and quite scary. We, as history educators, need to join conversations about the importance the social sciences have in the world. We need to engage our students in quality instruction and activities that look to the past in order to change our present and construct a better future. So what does inquiry look like and sound like in history classes? Here were some of our ideas. The post feels a little incomplete - but more to come once I try a few more of our ideas. Essential QuestionsAny quality unit must begin with an essential question. Many teachers use resources created by the Stanford History Education Group or the California History/Social Science Project to build tasks based on argumentative questions that examine historiography, attitudes and actions of historical figures, or the effects individual actions have on events. Each lesson in a unit should contribute to an understanding or deepening of knowledge related to the identified essential question. Classroom activities often revolve around the analysis of primary and secondary sources that provide varying perspectives and evidence to help construct some sort of response. Historical Thinking, Reading, & Writing SkillsThis chart, created by College Board, shows the historical skills that are assessed on Advanced Placement exams. They include skills that focus on thinking, reading, and writing. For decades, history pedagogy has been based on the idea that it's the teacher's responsibility to impart knowledge on students. Textbooks are set up this way. Assessments reflect the notion that history is an amalgamation of facts one needs to recall for multiple choice exams. In the last few years, the number of resources for a skills-based approach to history education have grown dramatically. We must be willing to admit that information is at our fingertips. When I am planning a lesson or when a student asks me a random question about some obscure fact, the first thing I want to do is consult my resources, i.e., just Google it. So why do we expect anything different from students? Historians don't work in disconnected spaces where they can't search for details or collaborate with peers to find the answers to a question. And yet, many students operate independently in history classes, quietly taking notes on a bunch of facts. A few years ago I decided that I would never force my students to copy down notes: why not just print them or make them available in digital form? I'd rather spend class time questioning, discussing, and applying the information. This doesn't mean I don't address confusing topics or ideas I consider to be extremely valuable. But I do spend time thinking about ways to communicate that information that is NOT in the form of a boring lecture using PowerPoint. I have toyed with the idea of video recording my lessons and then re-watching them. Would I want to be a student in my class? Showing LearningWriting in history classes might not happen too often, sans AP courses where argumentative writing is the foundation of most assessments. The introduction of writing might instill fear in history teachers, as I have heard many say, "I am not an English teacher." But we all practiced being historians. We all wrote essays in college. Teachers just have to reach back to their experiences as students and do a little more exploration about writing pedagogy in the social sciences. As more teachers and students embrace the model of writing encouraged by Document Based Questions, we can also consider alternatives to writing. At the high school level, we found that implementing long term PBL was difficult. This was particularly true for AP teachers. Even though the new frameworks allow for more opportunities to explore topics in more detail, the looming exam creates this kind of push to move through the content very quickly. We briefly talked about the skill of periodization and how students could show their learning by creating museum exhibits that represent significant artifacts that characterize a time period. This was something we all agreed to do some more reflecting about. One aspect that I think is missing my much of history pedagogy is discussion. I briefly explained the ideas behind emphasizing historical thinking, reading, and writing; however, research shows that our students do not talk enough. This includes formal academic/content language or informal speech. As multiple choice tests (hopefully) disappear from history classes, the question will be: what does authentic assessment look like in the social sciences? Historians, politicians, policy writers, economics, sociologists, and psychologists all ask questions in order to seek solutions. We must challenge ourselves to develop tasks that encourage students to create products that show reflection and forward thinking. What does speaking sound like in a history class? What does discussion let teachers know about students understanding of historical concepts? But this is an idea for a future post. Thanks - @historytechie @robertjmedrano @histcoach and many more for your ideas and inspiration for this post. Recommended ResourcesThis year I accepted a Teacher Technology Leader position at my site, which means I am responsible for supporting teacher's with educational technology alongside our instructional coach that helps with curriculum, instruction, and assessment. In the 10 years I have taught at the same site, there has never been a school-wide or district-wide effort to discuss technology use for learning. We have decided to start with SAMR, particularly since we just adopted Google Apps for Education for all teachers and students. One struggle that many teachers must face is the decision between using technology just because it's there and using technology because it enhances learning. Good pedagogy must come before inserting tech tools. Without clear learning objectives or ways to check for understanding, students are still going to struggle with content knowledge. These tools primarily focus on substitution and augmentation of content and skills that are often addressed in history classrooms. While not an exhaustive list, they are a few additions that engage students in historical thinking differently. If you have any suggestions, please add a comment. I am always looking to expand my teacher toolbox. HSTRYHSTRY is a great website for creating digital timelines. Unlike other web-based tools like Dipity or TimeToast, HSTRY allows for the integration of interactive tools embedded within the timeline. Images, videos, web-links, discussions, and quiz questions can be included to support the timeline content. Students can create timelines to review content or for a great review tool. Teachers can share timelines as a class activity where content and checking for understanding is part of the review process. The site is fairly easy to use and teachers can set up classes so that student work can be reviewed easily. There are some limits to the free version, but teachers or school sites can purchase a license for more advanced features. Docs TeachDocs Teach is hosted by the United States National Archive and is a great teaching tool that provides access to thousands of high quality primary source documents and skill-based lessons using the archived docs. The activity platform can be accessed through the website or through the iPad app. Teachers create lessons and students can join the activity using a classroom code. There are several different activities that emphasize different historical thinking skills including chronological thinking, historical analysis and interpretation, decision making, and weighing evidence. The activities can be used as an introduction to a unit whereby students engage in materials to build background information, or the document-based activities can be used as formative/summative assessment within a unit or at the end. The view tool allows students to zoom in on each document and there is also background information provided. MindmeisterMindmeister is another mind mapping tool - of which I know there plenty out there. However, what I like about this one is the user-friendly tools and the ability to integrate videos and images within the concept map. Then the map becomes interactive and allows students to move beyond the static page and make the content more visual to activate learning. Additionally, my site uses GAFE, which means I can send the app to all of my students using Google Play. They don't have to download or search - it's already there and ready for use. Google Art ProjectLike so many teachers, I can't afford to take my students on field trips to visit historical sites or museums. However, the Google Cultural Institute has made the idea of virtual field trips a possibility. Instead of showing students videos or pictures about the Palace at Versailles, they can actually walk through the Hall of Mirrors and wander the expansive gardens. They can enter the Uffizi galleries in Florence, Italy or the Musee D'Orsay in Paris, France. True, it's nothing like feeling the crisp air and the creative silence that fills the museum halls, but it's one virtual step closer to seeing artwork up close. Additionally, the Historical Moments gallery has collections about specific moments in time where pieces have been curated and explained. There is one about World War II told through 100 objects that is great. ThinglinkI learned about this tool from Liz Ramos in a presentation about visual literacy in history classes. Her website has a great example and links to sample unit/lesson plans using Thinglink. There are some drawbacks to the free version, but simply put, Thinglink allows students to conduct deeper analysis of images (photographs, paintings, drawings, etc.) by creating hyperlinks to their resources within the picture. The tool is great for political cartoon analysis because students can search for primary/secondary sources that support the cartoonist's perspective or attach videos related to the content. The image is layered with detail in an artistic sense and with Thinglink, with a historian's sense.

|

Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed