Why dystopia?Utopian and dystopian studies comes from a deeply historical context whereby people of all walks of life began imagining possible worlds where political, economic, and social conditions were altered. In United States history, utopian novels that were published during the antebellum age (1820s and 1830s) espoused the possibility to re-imagining social order. Communities built by the Shakers and Oneidas lived out their utopian dreams. Dystopian literature, burgeoning during the late 20th century reflected an increase in fear about political and economic turmoil. Novels like 1984 and Brave New World emphasized the relationship between power, technology, individualism, and conformity. Resistance and reform had a very different face after the social movements in the 1960s and 1970s. Dystopian novels play with constructs of time, space, history, and geography. The worlds seem so much like our own or at least what our world can be. While many of the novels written in the Cold War era reflect fears about conformity, dystopian novels written in the early 21st century engage these topics a little differently. Surveillance and ideological repression look different in 2015 than it did at the height of the Cold War. The battle between capitalism, socialism, and communism has been subsumed by neoliberalism and globalization. One person standing up for what they believe triggered marches and protests that were televised around the country in the 1960s and now one Tweet or YouTube video goes viral where the world is now watching global affairs. YA dystopian novels are unique in that they center on the actions of youth as they participate in resistance against totalitarian leaders. Each novel's world is constructed on some kind of sameness or conformity. The hero's or heroines never quite feel like they fit in with the communities expectations and they often find ways of escape expectation. Rather than accepting societies norms, that main characters question their world and seek alternatives. But no dystopian novel is "perfect," Some might say that the genre is itself a tool of resistance whereby authors offer social criticisms of our own world. However, a deeper analysis could reveal that the novels only reinforce some of the underlying economic and social tensions that youth experience today.

I believe that history teachers can use dystopian novels to help students see history in action. Sometimes history curriculum seems boring or outdated. Despite what some might say about the literary quality of some young adult novels, I find that dystopian fiction provides a doorway to connecting our students to our content. The language and vocabulary is similar between the novels and history curriculum. We can engage students in discussions about the past AND in imagining the future by integrating fiction into our classrooms. Books vs. FilmsAfter taking a Film & Literature course in college, I stopped making broad assumptions and arguments about whether or not the book or the movie was better. Essentially, it is like comparing apples to oranges. Privileging one over the other de-values both as artistic representations and tools of storytelling. Are there times where I enjoy the book more than the film, yes. But there are also films that do an amazing job in adapting novels so that my enjoyment and appreciation grows and changes. We have to view media as separate because they each have different goals and achieve those goals using different tools. We can study films in a similar way that we study novels by questioning narrative structure, format, characterization, and themes. Novelists work with words whereas film makers use music, sounds, and color to tell a story. Questions to be asked of dystopia & history curriculumPower

Knowledge

Surveillance Culture

Codification & Discrimination

Post-Capitalism & Consumerism

Novel ideas

Dystopian shortcomingsMy final thoughts come just after seeing the final installment of the Hunger Games films that opened this weekend. After reading 20+ dystopian novels (marketed for adults and youth), I have been left with one question: what happens after the rebellion? Almost all of the novels focus on resistance efforts led by characters who do not agree with the government's actions. But what is missing is any notion of HOW TO REBUILD. People join resistance movements to fight for their rights. Totalitarian governments are deposed. Evil leaders are killed. But the books and films always end there. There is no transfer of power. There is no explanation for what kind of society is re-imagined. The heros and heroines go home and live their lives out of the spotlight.

This feels exactly like a traditional history classroom. We spend time studying events of the past and do little to institute changes that will make the world more equitable. We fail to act on our knowledge in creating a better world. I love reading dystopian fiction because I get to engage in imaginative worlds that challenge me to think about our own. But we can't stop at resisting. We must also engage in creating and imagining.

1 Comment

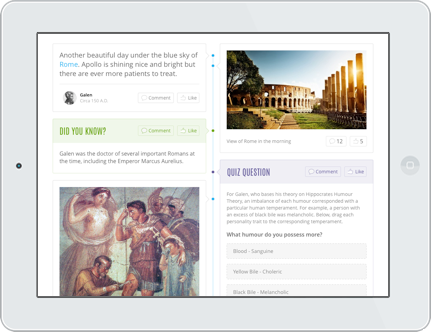

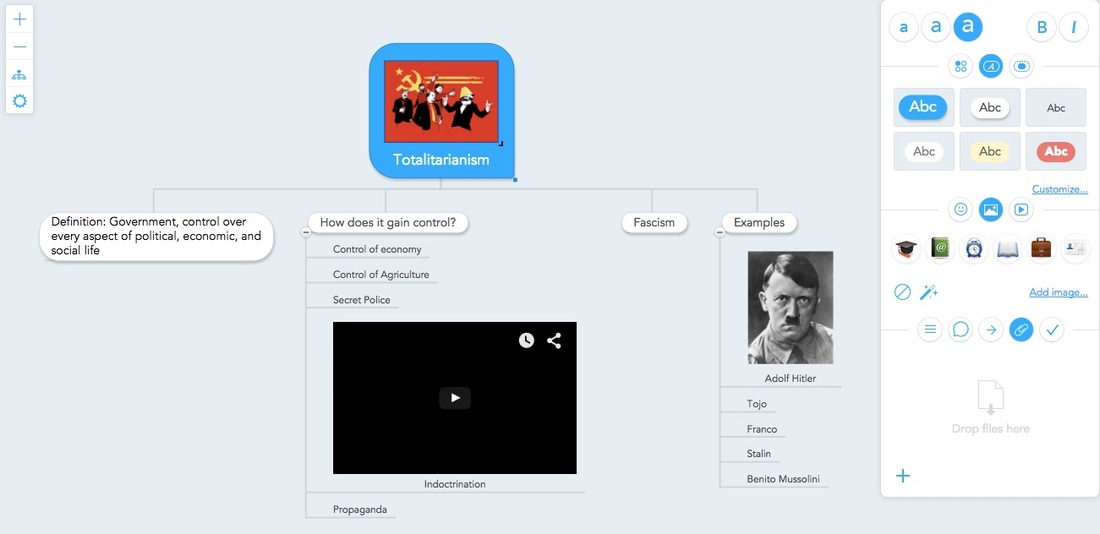

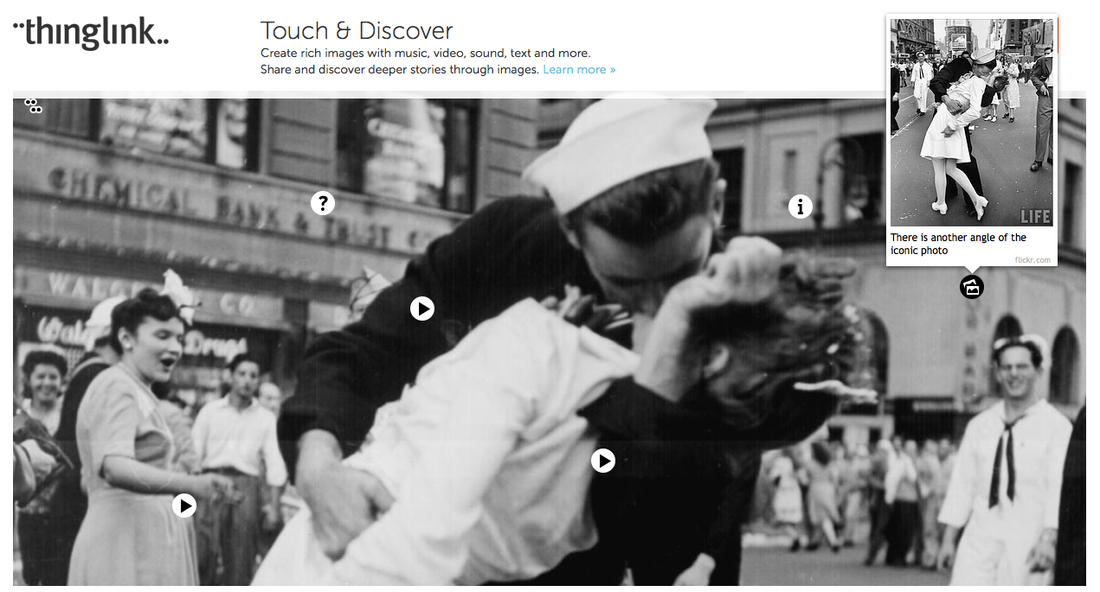

This year I accepted a Teacher Technology Leader position at my site, which means I am responsible for supporting teacher's with educational technology alongside our instructional coach that helps with curriculum, instruction, and assessment. In the 10 years I have taught at the same site, there has never been a school-wide or district-wide effort to discuss technology use for learning. We have decided to start with SAMR, particularly since we just adopted Google Apps for Education for all teachers and students. One struggle that many teachers must face is the decision between using technology just because it's there and using technology because it enhances learning. Good pedagogy must come before inserting tech tools. Without clear learning objectives or ways to check for understanding, students are still going to struggle with content knowledge. These tools primarily focus on substitution and augmentation of content and skills that are often addressed in history classrooms. While not an exhaustive list, they are a few additions that engage students in historical thinking differently. If you have any suggestions, please add a comment. I am always looking to expand my teacher toolbox. HSTRYHSTRY is a great website for creating digital timelines. Unlike other web-based tools like Dipity or TimeToast, HSTRY allows for the integration of interactive tools embedded within the timeline. Images, videos, web-links, discussions, and quiz questions can be included to support the timeline content. Students can create timelines to review content or for a great review tool. Teachers can share timelines as a class activity where content and checking for understanding is part of the review process. The site is fairly easy to use and teachers can set up classes so that student work can be reviewed easily. There are some limits to the free version, but teachers or school sites can purchase a license for more advanced features. Docs TeachDocs Teach is hosted by the United States National Archive and is a great teaching tool that provides access to thousands of high quality primary source documents and skill-based lessons using the archived docs. The activity platform can be accessed through the website or through the iPad app. Teachers create lessons and students can join the activity using a classroom code. There are several different activities that emphasize different historical thinking skills including chronological thinking, historical analysis and interpretation, decision making, and weighing evidence. The activities can be used as an introduction to a unit whereby students engage in materials to build background information, or the document-based activities can be used as formative/summative assessment within a unit or at the end. The view tool allows students to zoom in on each document and there is also background information provided. MindmeisterMindmeister is another mind mapping tool - of which I know there plenty out there. However, what I like about this one is the user-friendly tools and the ability to integrate videos and images within the concept map. Then the map becomes interactive and allows students to move beyond the static page and make the content more visual to activate learning. Additionally, my site uses GAFE, which means I can send the app to all of my students using Google Play. They don't have to download or search - it's already there and ready for use. Google Art ProjectLike so many teachers, I can't afford to take my students on field trips to visit historical sites or museums. However, the Google Cultural Institute has made the idea of virtual field trips a possibility. Instead of showing students videos or pictures about the Palace at Versailles, they can actually walk through the Hall of Mirrors and wander the expansive gardens. They can enter the Uffizi galleries in Florence, Italy or the Musee D'Orsay in Paris, France. True, it's nothing like feeling the crisp air and the creative silence that fills the museum halls, but it's one virtual step closer to seeing artwork up close. Additionally, the Historical Moments gallery has collections about specific moments in time where pieces have been curated and explained. There is one about World War II told through 100 objects that is great. ThinglinkI learned about this tool from Liz Ramos in a presentation about visual literacy in history classes. Her website has a great example and links to sample unit/lesson plans using Thinglink. There are some drawbacks to the free version, but simply put, Thinglink allows students to conduct deeper analysis of images (photographs, paintings, drawings, etc.) by creating hyperlinks to their resources within the picture. The tool is great for political cartoon analysis because students can search for primary/secondary sources that support the cartoonist's perspective or attach videos related to the content. The image is layered with detail in an artistic sense and with Thinglink, with a historian's sense.

|

Archives

January 2019

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed